National Trust Residency at the Cabin in Bucks Mills, North Devon. 8th – 13th September 2015

I arrived in Bucks Mills late on Monday 7th of September to begin a residency in the Cabin, culminating in two open days at the weekend. The village of Bucks Mills is set within a combination of ancient woodland and rocky coast and has a rare wildness not so often found in the UK. The village winds down a wooded valley from the main road and finishes in a small square, pretty much on the edge of a cliff. Beyond it is the Atlantic. A path leads steeply down to a pristine stony beach and located near the beginning of the path, high up over the sea, is the Cabin. It is a small stone structure that was used between the 1920s and 1970s by the artists Judith Ackland and Mary Stella Edwards who lived and worked there for sustained periods. In 1971 they locked up the Cabin leaving it ready for their next visit. However, Judith died later that year and Mary, devastated at her death, never returned. Afterwards she decreed that it should be left just as it is, as a tribute to their creative lives together.

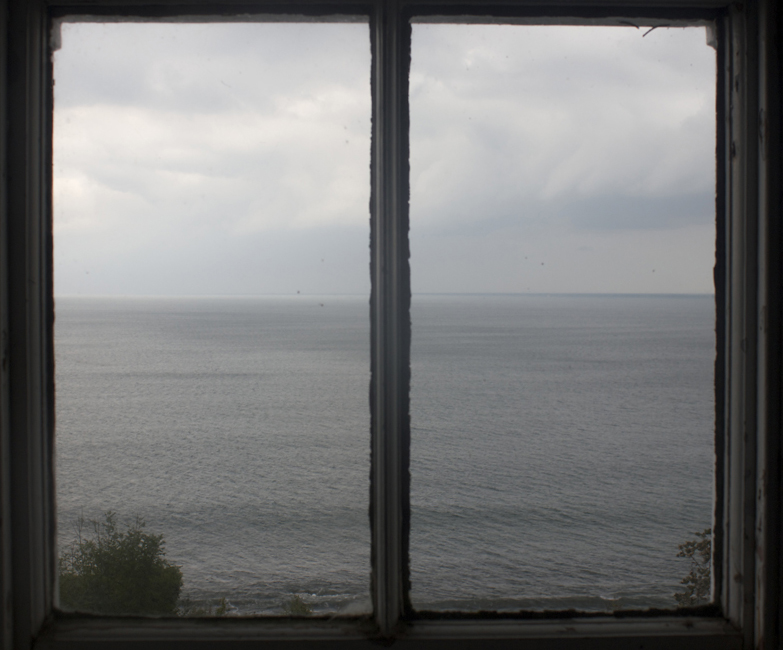

The Cabin is tiny, teetering on the edge of the cliff. It is a time capsule and, as such, a resonant reminder of the fragility and temporality of individual life and creativity. But what impacted on me more was the character of loss that it embodies. You walk into the shared life of these two women – yet the space has been still for at least 40 years. The windows, especially upstairs, are filled by the sea. You can hear its motion, and that of the waterfall nearby whilst at the same time you are transfixed by the silence reverberating in the stasis of a space that has not been occupied, apart from by visitors and the occasional artist in residence, since 1971.

Some things are familiar. For me, seeing on the windowsill the dead Peacock butterfly among dusty stones and shells reminded me of my grandmother’s Suffolk house, back in the 1970s. The upstairs loo (‘the aunt’ she called it) often had a host of these butterflies on the window ledge – dead, their beautiful wings tangled in cobwebs and sunlight filtering through the dust, the stillness and timelessness somehow giving rise to the illusion of permanence, but at the same time serving as a reminder that loss is irrevocable. This relationship and the presence of the sea fascinated me. The sea was so vast, beautiful and manifestly present that although you couldn’t say it filled up the space of that loss, it contested it and created a powerful juxtaposition.

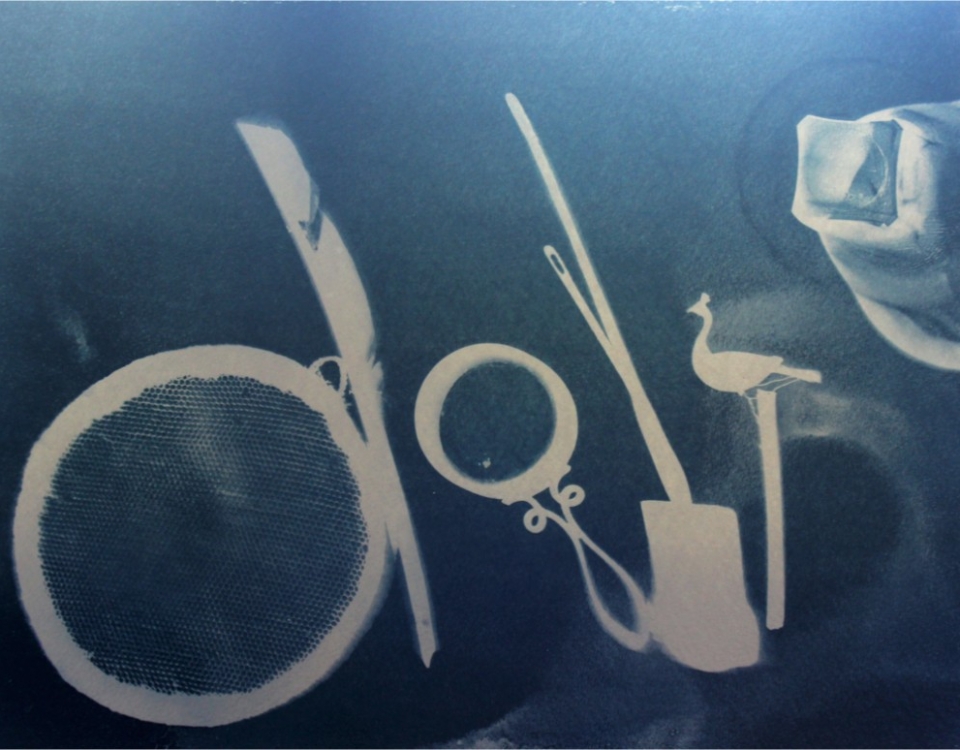

The women owned an astonishing array of unusual objects which they managed to fit in alongside their day to day crockery and utensils. Surprisingly, the hut does not feel crowded, and upstairs is remarkably spacious with a lovely quality of light. I did a cyanotype (a version of camera-less photography) of a collection of their objects intending to do a series, but in the end made only one because oddly I found I didn’t want to disturb the things in the house – even to borrow them for a moment to rearrange them for a cyanotype. It felt a bit like T. S. Eliot’s “Disturbing the dust on a bowl of rose leaves” from Four Quartets. They just needed to be left. Or picked up, mulled over, wondered at and then returned to where they belong – back to dusty box or drawer or rusty nail. They are part of the Cabin’s narrative and there they remain.

On arriving, I wasn’t sure how I would work. I had long been drawn to this part of coastal North Devon and now own a cottage in Bucks Mills. This was where I slept as you cannot stay overnight in the Cabin. I therefore had space to spread things around, as well as ready access to water and other essentials including the chemicals necessary for photographic processes. I had proposed seeing the few days as a staged encounter with the ocean – but of course these preparations were confounded as soon as I stepped through the Cabin door. Other ideas began to form.

Waterdrawings of plants with soil and gum

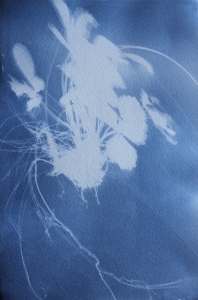

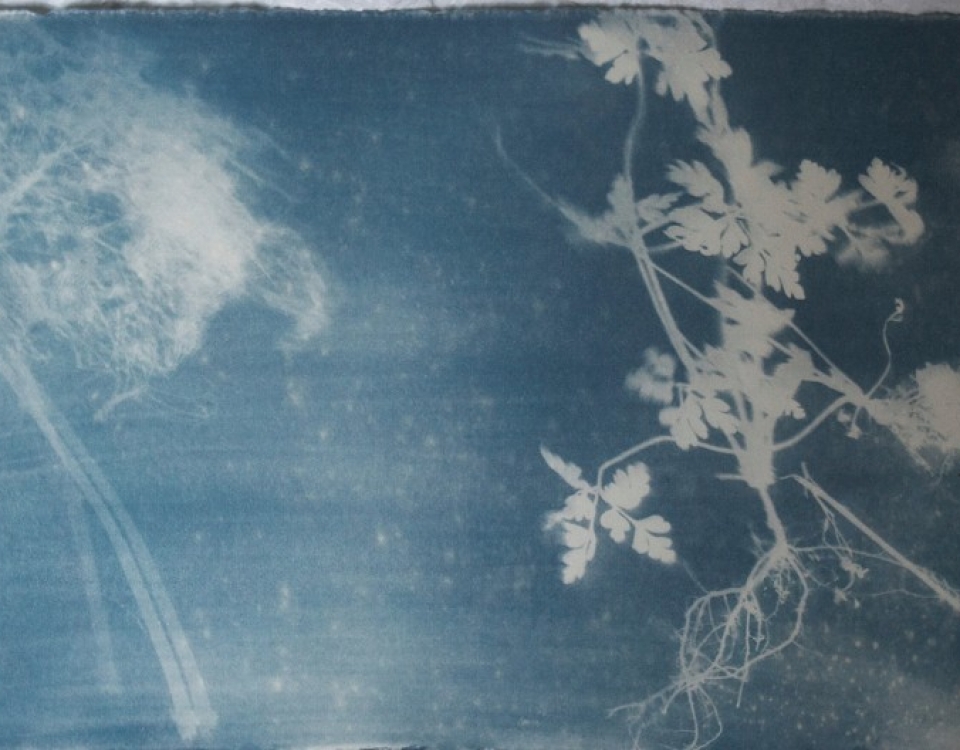

I tried various methodologies – watercolour sequences inspired by the stretch of the sea visible from the upstairs window, water drawings of local plants with pipettes – and then I turned to cyanotype and worked directly with light using plants found near the house and beach. I had brought with me books: Ocean Flowers: Impressions from Nature, the Photograms of Anna Atkins and others; Thinking is Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys; and, most productively, Every Day is a Good Day: The Visual Art of John Cage.

Cabin plant series – cyanotypes from plants around the Cabin

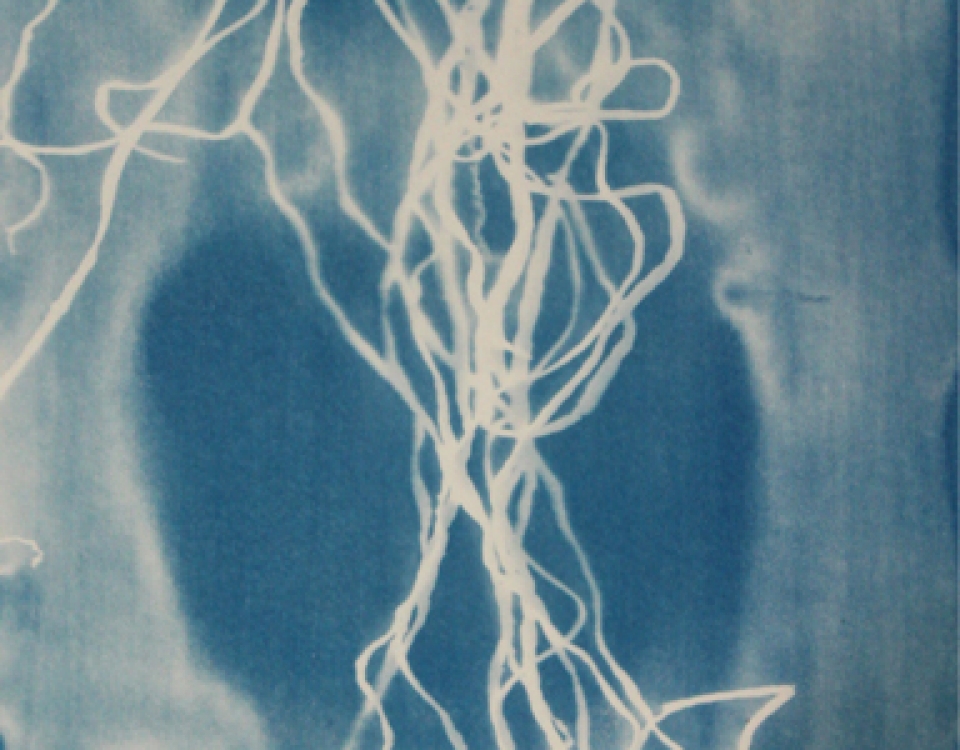

I had always been interested in John Cage’s “chance procedures” in his visual art, a method devised to create images that contrive an element of chance in their making. It is part of my ongoing interest in making work that facilitates nature and creates space for natural processes as part of its strategy. Cage deployed various chance-inducing systems including the I Ching. I used dice, the number thrown dictating my action.

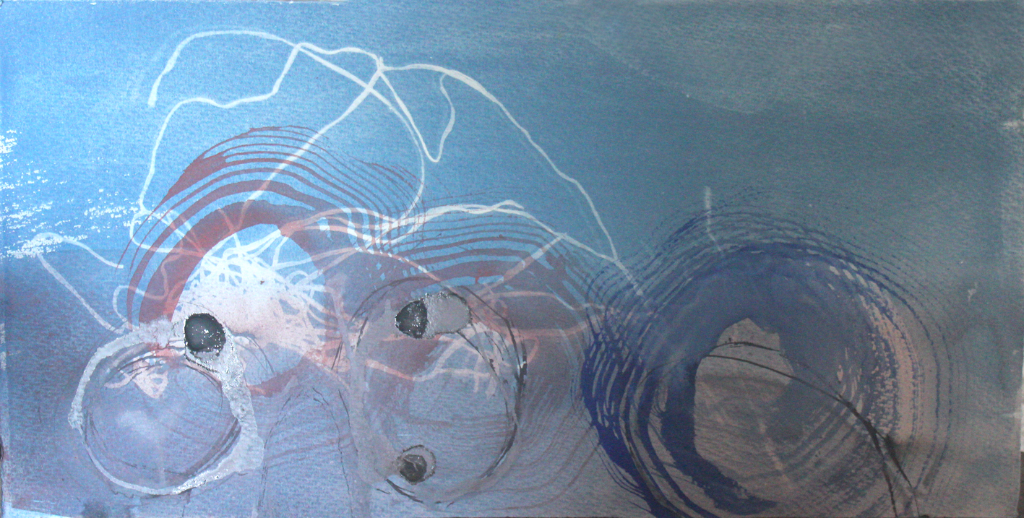

I decided on a sequence that would start with a cyanotype of local plants or seaweed. The next stage involved stones from the beach chosen by dice and rolled more or less randomly onto the surface and then outlined with feather, string or pipette – depending on the dice – followed by applications of paint with various instruments or by dipping the paper into trays of watery colour and letting puddles form and dry.

On the one hand, seeing the plants reveal complex and delicate shapes in the cyanotype process was wonder enough. Some I kept without further work, for instance a sequence of a group of plants gathered early one morning from around the Cabin (including wild strawberries that the artists may have planted themselves). Others were the starting point for experiments with chance procedures.

chance procedure i, cyanotype

chance procedure i, cyanotype

further chance procedures

I was glad that the cyanotype works on paper that I developed with paint took on a watery look, as if submerged in water or within a moving river. In my paintings generally, the use of water is key not just in the materials and how they puddle, layer and dry, but also in the expressive potential that water in nature has to signify states of being, looming clouds, saturation or light diffused through mist. In the Cabin the presence of the ocean was always there, inflecting everything, through every window – a vast undulating field of light.

The residency at the Cabin was an opportunity to encounter and find ways to work with nature, which is the continuing theme of my work. It is also the beginning part of a longer project that I’m envisaging, engaging further with nature in the area and also a prelude to a residency I will be taking up this December for a month in the rainforest of Peru, encountering a very different kind of nature and place. It occurs to me that water will play a large part there too. As well as the intense nature that I am going there to experience, it will be the rainy season and I adore the rain.

Open day, September 13th

Residency courtesy of the National Trust

The Cabin, Bucks Mills, North Devon EX39 5DY

0 Comments

Comments are closed.